Environmental and workplace exposure to pesticides

Environmental and workplace exposure to pesticides

Pesticides are a group of chemical compounds used to manage and kill pests, such as weeds, fungi, insects, and rodents.[1] Globally, more than 4 billion kilograms of pesticides are used every year to increase food production and prevent spoilage.[2] Over 130 million kilograms of pesticides are sold in Canada annually, the majority of which is sold for agricultural use (approximately 70%).[3] Several pesticides such as aldrin, chlordane, and DDT have been banned due to their toxicity, however many of them are still found in our air, soil, and water.[4]

The majority of pesticides that are currently used in Canada are classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as either probably or possibly carcinogenic to humans (Group 2A and 2B), or not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans (Group 3).[5] However some IARC known carcinogens (Group 1) are still present in the Canadian environment and workplaces despite being banned (i.e. DDT) or restricted in use (i.e. lindane, pentachlorophenol). Cancers linked to pesticides include non-Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, prostate, testicular, pancreatic, lung, and non-melanoma skin cancers.[6,7,8]

CAREX Canada’s resources on exposure to pesticides

CAREX Canada has developed the following resources to help characterize Canadians exposures to pesticides:

Profiles

We offer profiles for a number of pesticides that Canadians may be exposed to. The profiles provide general information about each pesticide, the health effects, the regulations and guidelines related to exposure in Canada, the main uses, and an overview of exposures in workplaces and community environments. They can be accessed on our Profiles & Estimates page by selecting Pesticides from the list of categories.

Occupational exposure estimates

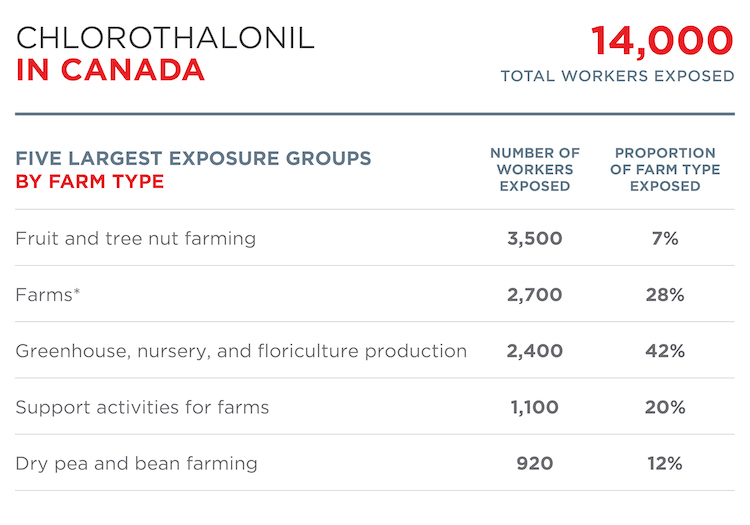

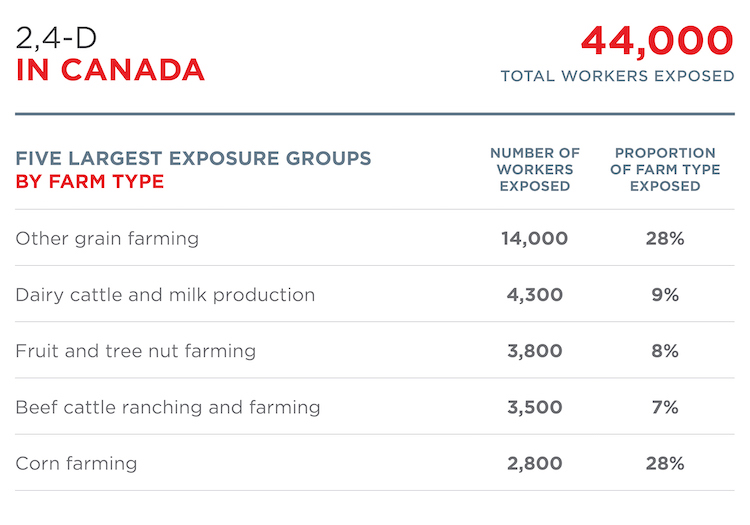

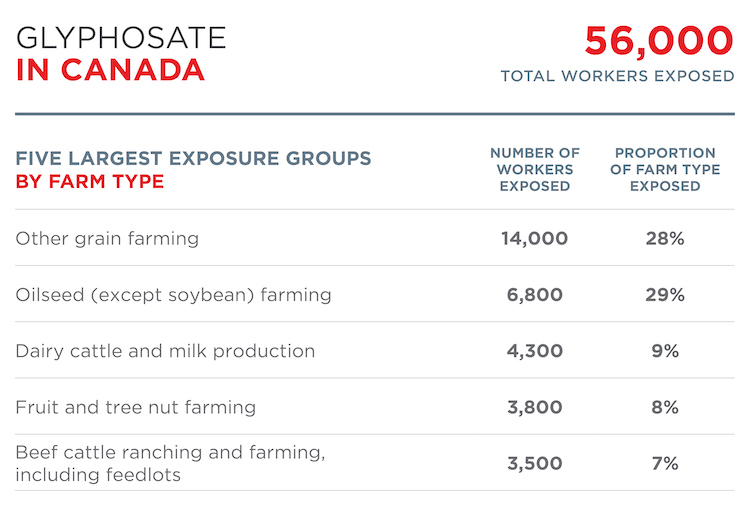

These estimates show the number of workers exposed to chlorothalonil, 2,4-D, and glyphosate in the agricultural industry, as well as breakdowns by farm type and region.[9] Occupational exposure was estimated for the agricultural industry specifically, since the majority of sales by weight is for agricultural use.

Environmental exposure estimates

We offer two distinct types of environmental exposure estimates for pesticides: potential exposure and lifetime excess cancer risk.

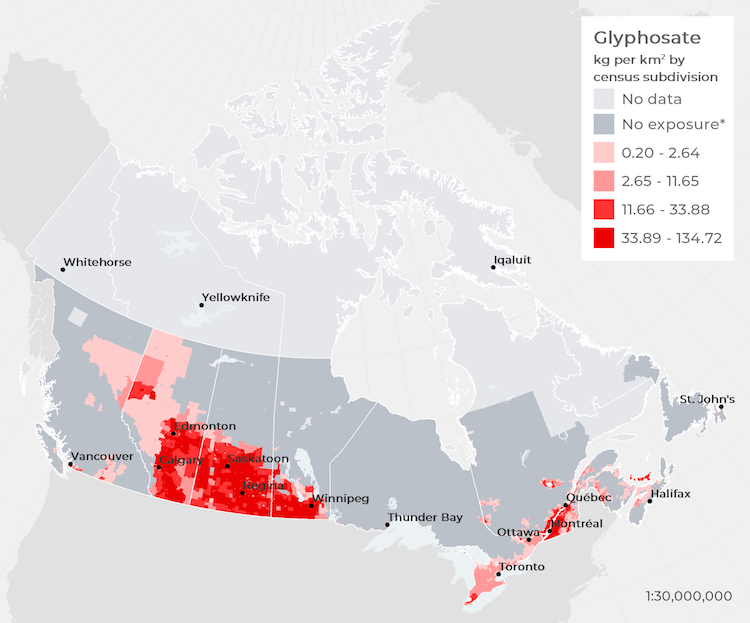

(1) Potential exposure: These estimates (circa 2016) show the number of people potentially exposed to each pesticide by region based on their residential proximity to agricultural areas, as well as national maps of estimated agricultural pesticide usage.[10] In Canadian communities, we estimate that:

- Over 1.5 million people live in areas with higher potential for chlorothalonil exposure

- Over 2 million people live in areas with higher potential for 2,4-D exposure

- Over 2 million people live in areas with higher potential for glyphosate exposure

(2) Lifetime Excess Cancer Risk: These estimates (circa 2011) use lifetime excess cancer risk as an indicator of Canadians’ exposure to known or suspected carcinogens in the environment. We offer estimates of daily intake and cancer risk for chlorothalonil, dichlorvos, lindane, and pentachlorophenol.

Publications

These peer-reviewed articles provide details on our environmental and occupational exposure estimates for pesticides:

- Rydz CE, Larsen K, Peters CE. “Estimating Exposure to Three Commonly Used, Potentially Carcinogenic Pesticides (Chlorolathonil, 2,4-D, and Glyphosate) Among Agricultural Workers in Canada.” Ann Work Expo Health 2020.

- Larsen K, Black P, Rydz E, Nicol AM, Peters CE. “Using geographic information systems to estimate potential pesticide exposure at the population level in Canada.” Environ Res 2020;191:110100.

Dietary pesticide exposure

People living in proximity to agricultural land may have higher pesticide exposures due to potential consumption of contaminated water, inhalation as a result of application or drift, and/or direct contact with dust.[11] However, the primary route of exposure to most pesticides among the general population is dietary intake.[12] More than 85% of conventionally grown fruits and vegetables in the U.S. tested positive for pesticide residue.[13] Organically grown fruits and vegetables contain less pesticide residues than their conventionally grown alternatives,[14] but pesticide contamination may occur from spray-drift or aerial spraying in nearby fields or use of contaminated water.[15] Foods may also become contaminated after harvest if they are stored or transported with conventionally grown produce, or in an area that has been treated with pesticides.[14] In addition, meat, dairy, and seafood may also contain pesticide residues from their food sources and environment, which can accumulate in the animal’s fat.[16]

Despite the ubiquity of pesticide use in the agricultural sector, most fruits and vegetables have pesticide residues well below the legislated, maximum allowable level.[17] In Canada, less than 2% of domestically grown and 7% of imported fruits and vegetables tested contain pesticide levels above the maximum allowable level.[17]

Reducing exposure to pesticides in food

Fruits and vegetables are integral to a healthy diet as they provide antioxidants, fiber, and essential nutrients and should be consumed daily.[18] Low consumption of fruits and vegetables is itself a risk factor that contributes significantly to the burden of cancer.[19] The health benefits of consuming fruits and vegetables (whether conventionally grown or organic) far exceed the health risks associated with dietary intake of pesticides.[20]

However, there are several ways to minimize this exposure. Rinsing produce under running water for a minimum of 30 seconds to two minutes in combination with rubbing or scrubbing, blanching or boiling the produce, or soaking it in water solutions (with salt, vinegar, or baking soda) are all effective ways to reduce surface pesticides, although the efficacy varies depending on the fruit/vegetable and the specific pesticide.[21] Peeling is the most effective way to remove surface pesticides; however, this can lead to the loss of beneficial compounds that are present in the peels of some produce such as apples.[22]

Trimming the fat from meat can also reduce exposure, as pesticides can concentrate in the fat of animals.[23] If consumers wish to prioritize purchasing some organic fruits and vegetables, foods with an edible exterior (e.g. apples, zucchinis, grapes) are a good choice. Foods with inedible outer layers (e.g. bananas, mangos) carry a lower risk of pesticide exposure because the peel is removed before eating.[21]

References and other resources

Sources

Other resources

Prevention Policies Directory: We also recommend exploring the Prevention Policies Directory, a freely-accessible online tool offering information on policies related to cancer and chronic disease prevention. Providing summaries of the policies and direct access to the policy documents, the Directory allows users to search by carcinogen, risk factor, jurisdiction, geographical location, and document type. For questions about this resource, please contact a member of the Prevention Team at the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer at primary.prevention@partnershipagainstcancer.ca

Subscribe to our newsletters

The CAREX Canada team offers two regular newsletters: the biannual e-Bulletin summarizing information on upcoming webinars, new publications, and updates to estimates and tools; and the monthly Carcinogens in the News, a digest of media articles, government reports, and academic literature related to the carcinogens we’ve classified as important for surveillance in Canada. Sign up for one or both of these newsletters below.

CAREX Canada

School of Population and Public Health

University of British Columbia

Vancouver Campus

370A - 2206 East Mall

Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z3

CANADA

As a national organization, our work extends across borders into many Indigenous lands throughout Canada. We gratefully acknowledge that our host institution, the University of British Columbia Point Grey campus, is located on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) people.