Artificial UV Radiation Profile

RADIATION – KNOWN CARCINOGEN (IARC 1)

Contents

Artificial UV Radiation Profile

QUICK SUMMARY

- Radiation emitted by artificial sources, found between visible light and x-rays on the electromagnetic spectrum

- Associated cancers: Skin cancer, ocular melanoma

- Most important routes of exposure: Skin or eye contact

- Uses: Electric welding arcs, curing lamps to harden resins and paints, germicidal lamps for sterilization, lasers, tanning beds, and in medical and dental practices

- Occupational exposures: Approx. 133,000 Canadians workers are exposed at work, primarily welders

- Environmental exposures: Indoor tanning facilities

- Fast fact: Between 2011-2016, all ten Canadian provinces and one territory (NT) passed legislation to ban tanning bed use by minors under the age of 18 or 19.

General Information

On the electromagnetic spectrum, ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is found between visible light and x-rays. It is divided into three components: UV-A (315-400 nm), UV-B (280-315 nm) and UV-C (100-280 nm).[1,2] Studies show that UV-C is the most genotoxic of the three components, while UV-A is the least.[2] Artificial sources of UVR emit a range of wavelengths specific to each source.[3] Artificial UVR may be used in occupational settings (medicine, industry, business and research) as well as for cosmetic and domestic purposes (sunlamps and sunbeds).[3] Welding arcs and UV lasers are also sources of artificial UVR.[4]

UVR with wavelengths in the range of 100 to 400 nanometres (nm; including UVA, UVB, and UVC), including UV-emitting tanning devices and UVR from welding, have been classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as Group 1, known human carcinogens.[5,6] There is sufficient evidence that artificial tanning devices cause skin and ocular melanoma; the risk of developing melanoma was prominently and consistently increased in people who first used the equipment in their twenties or teen years.[3] There is also sufficient evidence that UVR exposure from arc welding increases the risk of ocular melanoma.[6] Fluorescent lights also emit UVR.[2] Studies examining the relationship between melanoma of the skin and exposure to fluorescent lights at work have produced conflicting results and fluorescent lights were classified by IARC as Group 3, not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans.[1,7]

As with solar UVR, exposure to artificial UVR may result in short term skin damage such as burning, fragility, and scarring; in addition to carcinogenic effects, long term exposures may break down collagen and decrease skin elasticity.[8] Data suggest that using indoor tanning facilities may produce detrimental effects on the skin’s immune response.[3] Using certain prescription drugs or exposure to industrial chemicals such as coal tar distillates may cause hypersensitivity to UVR.[4] Fair skinned individuals are at greater risk of adverse outcomes following UVR exposure.[9] UVR generated from arc welding can cause various eye disorders, such as cataracts or keratoconjunctivitis, in both welders and nearby workers.[6]

Regulations and Guidelines

Occupational Exposure Limits (OEL)

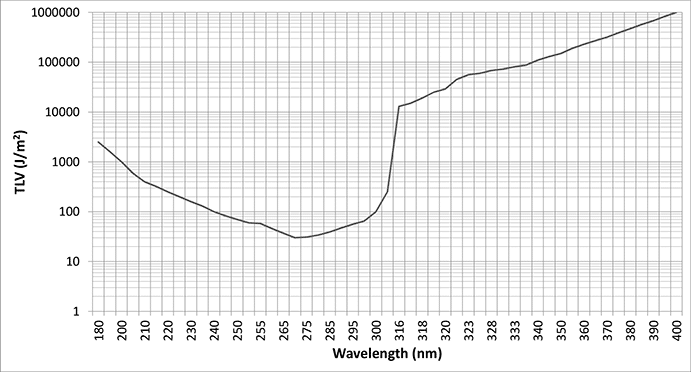

The American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) recognizes ultraviolet radiation as an occupational hazard and recommends different exposure threshold limit values (TLVs) for different UVR wavelengths in air between 180 and 400 nanometres.[10] The recommended TLVs published in 2015 are shown in the figure below.

J/m2 = Joules per square metre

Canadian regulations and guidelines

| Regulation/guideline | Year |

|---|---|

| Radiation Emitting Devices Act | 1985[11] |

| Regulation Amendment: Radiation Emitting Devices Regulations (Tanning Equipment) | 2005[12] |

| Skin Cancer Prevention (Artificial Tanning) Act (AB) | 2018[13] |

| Guidelines for Tanning Salon Owners, Operators and Users | 2014[14] |

| Food and Drugs Act: Medical Devices Regulations | 1998[15] |

| The Public Health Amendment Act (Prohibiting Children’s Use of Tanning Equipment and Other Amendments) (MB) | 2016[16] |

| Tanning Beds Act (NS) | 2010[17] |

| Artificial Tanning Act (NB) | 2013[18] |

| Radiological Health Protection Act (NB) | 1992[19] |

| Radiation Health and Safety Regulations (SK) | 2005[20] |

| Guidelines for Tanning Salon Operators (BC) | 1997, 2004[21] |

| Skin Cancer Prevention Act (Tanning Beds) (ON) | 2013[22] |

| Personal Services Act (NL) | 2014[23] |

| Act to Prevent Skin Cancer Caused by Artificial Tanning (QC) | 2013[24] |

Main Sources of Artificial UVR

Electric welding arcs can produce significant levels of UVR within a radius of several metres; gas welding and cutting torches do not produce high levels of UVR.[4]

Artificial UVR is used in medical and dental practices for procedures such as treating skin diseases and neonatal jaundice, detecting and treating cavities, and managing chronic conditions such as seasonal affective disorder (SAD) and sleep disorders.[3]

Curing lamps emit intense artificial UVR to harden resins and dry paints; these processes are usually enclosed but openings in the enclosure may lead to overexposure.[4] Germicidal lamps, commonly used to sterilize materials in hospitals, are strong emitters of UV-B and UV-C radiation.[4] Halogen, xenon, and metal halide lamps can emit artificial UVR; however, black lights, incandescent, and fluorescent lamps do not generally present a high exposure risk.[4] Ultraviolet lasers, which emit a single invisible wavelength of UVR, are used industrially and medically.[4]

Environmental Exposures Overview

Cosmetic tanning appliances, which may be referred to as sunbeds, sunlamps, or tanning beds, are the main source of artificial UVR exposure for the general public.[1,3] Estimates show that powerful tanning units may emit UVR with an intensity 10-15 times greater than that of the midday sun.[3,25]

Current tanning appliances primarily emit UV-A radiation,[1,26] although recently tanning lamps have been manufactured to produce higher levels of UV-B in order to mimic the solar spectrum and speed up the tanning process.[6,27] Indoor tanning facilities are most commonly used by younger women (17-21 years) in North America.[28]

The Canadian Cancer Society has endorsed the World Health Organization’s recommendation that no person under 18 should use artificial tanning equipment.[29] Between 2011 and 2016, all ten Canadian provinces and one territory (NT) have passed legislation to ban the use of tanning beds for minors under the age of 18 or 19.[30,31,32,23,33,34,35,22,36,24,37]

Occupational Exposures Overview

Exposure to artificial UVR may be dermal or ocular.

CAREX Canada estimates that approximately 133,000 Canadians are likely exposed to artificial UV radiation in their workplaces. The largest industrial groups exposed repair and maintenance (includes welding), fabricated metal product manufacturing, and personal and laundry service. The largest occupational group exposed is welders and related machine operators. Other exposed occupations include animal health technologists and veterinary technicians, medical laboratory technologists, and managers in customer and personal services.

Other occupations with potential for exposure to artificial UVR include tanning appliance operators, as well as workers in industrial photo-processes, sterilization and disinfection (sewage effluents, drinking water, swimming pools, operating rooms and research laboratories), non-destructive testing, printing, phototherapy, UV photography, UV lasers, food industry quality control, and discotheques.[3,4,38]

According to the Burden of Occupational Cancer in Canada project, occupational exposure to artificial UV radiation leads to approximately 15 ocular melanoma cancers each year in Canada, based on past exposures (1961-2001).[39,40] This amounts to 5.4% of all ocular melanoma cancers diagnosed annually. Most artificial UV-related cancers occur among welding-related jobs in the manufacturing, trade, and construction sectors.[40]

Artificial UVR exposure may be mitigated through engineering controls (such as enclosures), however in some applications workers can be exposed by reflection or scattering from adjacent surfaces, a phenomenon that is particularly concerning for tanning appliance operators.[3]

For more information, see the occupational exposure estimate for UV radiation.

Sources

Other Resources

- European Union. Scientific Committee on Consumer Products (SCCP) Opinion on Biological effects of ultraviolet radiation relevant to health with particular reference to sunbeds for cosmetic purposes (2006) (PDF)

- Health Canada. Frequently Asked Questions on the Radiation Emitting Devices Regulations (Tanning Equipment) (2007)

Subscribe to our newsletters

The CAREX Canada team offers two regular newsletters: the biannual e-Bulletin summarizing information on upcoming webinars, new publications, and updates to estimates and tools; and the monthly Carcinogens in the News, a digest of media articles, government reports, and academic literature related to the carcinogens we’ve classified as important for surveillance in Canada. Sign up for one or both of these newsletters below.

CAREX Canada

School of Population and Public Health

University of British Columbia

Vancouver Campus

370A - 2206 East Mall

Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z3

CANADA

As a national organization, our work extends across borders into many Indigenous lands throughout Canada. We gratefully acknowledge that our host institution, the University of British Columbia Point Grey campus, is located on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) people.